unmasking the arts

What does the future hold for the arts when British society starts to 'unmask' and return to some version of normal? Unmasking the Arts is a love letter to the British creative industries – dance, drama, music, cinema and more – that once thrived and, with the right investment, will once again. The creative industries can provide collective and individual catharsis as we move forward, empowering people to find joy once again.

From virtual museums to socially distanced gigs and the best way to reinvigorate the industries to how tastes will change in the coming months, we’ve aimed to spotlight the exciting opportunities and challenges UK arts will face. As we were completing this project, the government announced a further £408m boost for the struggling culture sector, in addition to the £1.5bn already announced. Whilst this is a welcome announcement for many, questions remain about how the arts sector is valued within our society.

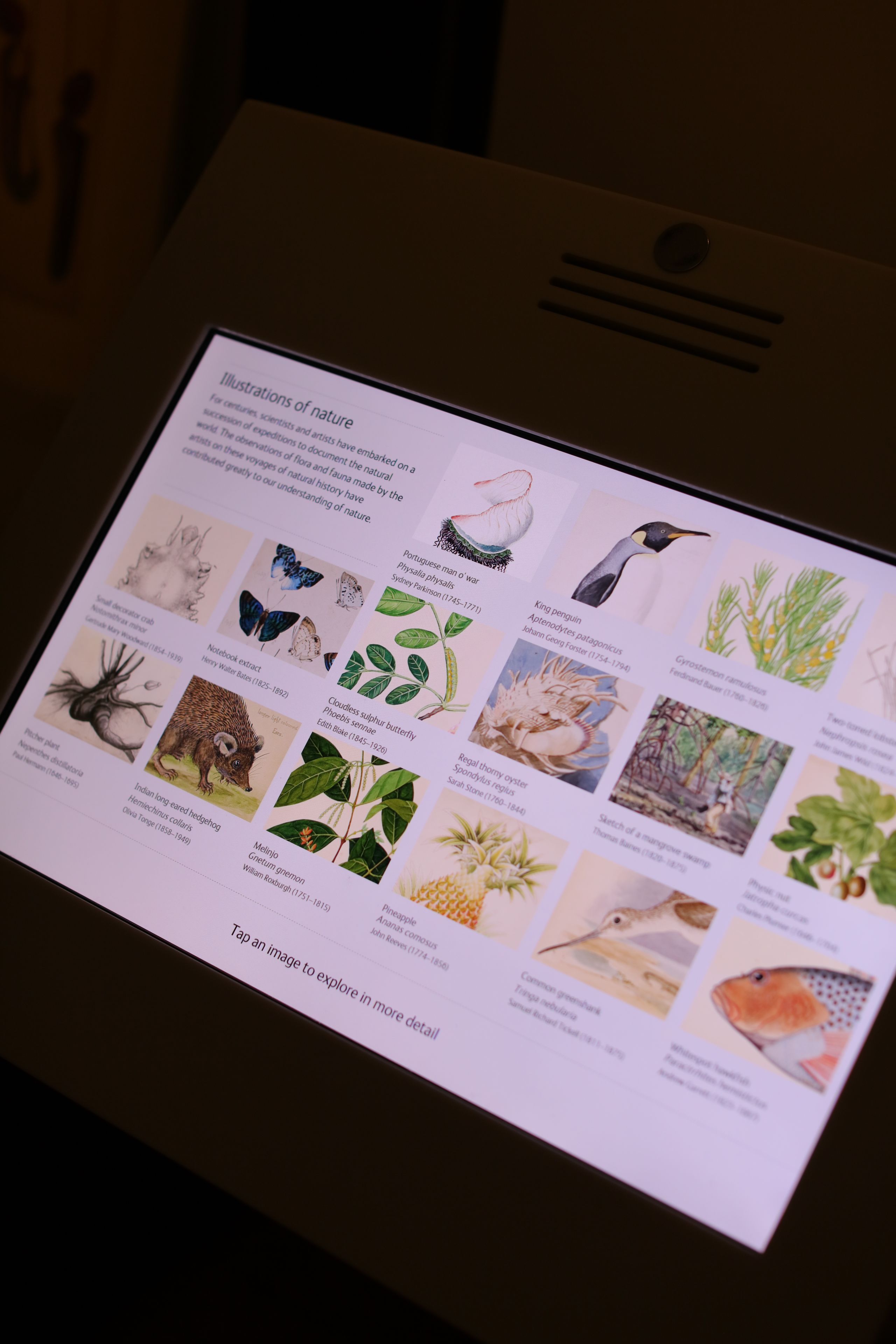

Is the Future Virtual for the UK’s Galleries and Museums?

In a post-Covid future, we can look forward to a blended offer from museums and galleries, as well as a smarter virtual experience.

By Yomika Wei

As soon as coronavirus started shutting down arts museums and galleries in the United Kingdom, there were growing fears among curators and directors about their ability to attract visitors back after the restrictions were lifted. Meanwhile, consumers’ appetites for online art experiences—picture galleries, artist talks, curator lectures, virtual tours— are booming, with people able to enjoy their favourite artwork from the comfort of their own homes. While the situation is a devastating blow for many, it also offers many opportunities. Rather than talking about how technology makes art more accessible, both audiences and organisations are being forced to embrace it. How the digital technology of galleries and museums in the UK will continue to change amid the new normal of a post-COVID society is a conundrum for all art lovers and practitioners.

The digital culture we now live in is changing every aspect of our lives. In our daily life, we are surrounded by technology, whether in homes, offices, supermarkets, and boutique stores, where almost every aspect of planning, design, marketing, distribution, logistics, and management is operated or controlled digitally. When the lockdown started, a great number of art galleries and museums in the UK moved swiftly to place huge swathes of their business online. According to the COVID-19 IMPACT Museum Sector Research Findings Summary Report by the Art Fund, the vast majority of organisations (86%) have increased their online presence and the amount of their content available online, with less than half having seen an increase in online visitors to their websites.

Countless art museums and galleries around the UK used this time to innovate and to put into effect schemes to make artworks and exhibitions available to explore on a digital platform. The National Gallery in London offers more than 2,600 paintings for people to search, browse and view on its website. The British Museum lists 11 ways that audiences can participate in the museum experience from home. One of the most popular is its Virtual Museum tours via Google Street View, as the world’s largest indoor space offers the opportunity to discover objects such as the Rosetta Stone in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery. Hastings Contemporary offers tours facilitated by telepresence robots developed by Double Robotics. Based on the overwhelmingly delighted interest in these Robot Tours, Liz Gilmore, the director of Hastings Contemporary commented: “Not only will we be sharing images, video content, interviews and information from our past, current and future exhibitions, but we’ll also be expanding the very limits of what it means to be an art gallery in the future.”

Compared with the national museums funded by the government, independent art galleries and museums appear to be in the most immediate need of financial and technical assistance. Some curators have voiced concerns that, “Because we don’t have a team, a digital media team, we don’t have a collection online yet, we can’t jump on board that opportunity of all the digital stuff that’s going on…we can’t brainstorm about what amazing digital projects we can do, because nobody can do it.” Luckily, some of the small private galleries received extra support from organisations such as the internationally renowned Art Basel, and have launched online viewing rooms. Others have gone further and developed digital and immersive technology in order to overcome the current situation. Although, some of these should be adopted as a more long-term solution to make art and culture more accessible to the masses.

In recent months, digital engagement and cultural heritage have been the top priorities for museums and galleries. It is recognised that these provide an opportunity to bring people together, encouraging creativity, sharing ideas and offering a virtual place for communication. There are tangible obstructions in the way of such a scheme, including consideration of how best to use novel technology to spread information between users, methods by which a traditional institute can gain or maintain contemporary relevance, ways in which to recognise the dynamic innovations that are appearing in the world of art, and solutions to bringing them into the public eye in a safe and timely manner.

There are certainly advantages and disadvantages to moving online. We may not know what the museums and galleries in the United Kingdom will look like in this unprecedented moment. In a post-Covid future, we can look forward to a blended offer from art museums and galleries, as well as smarter virtual experiences. The opportunity can be seen if we take a slightly longer view—people will have a safe, inclusive, and welcoming environment once museums and galleries are out of lockdown, while also having more opportunities to participate in art exhibitions, talks, and activities with these institutions in their cozy living rooms.

Image credit: Yomik Wei

Image credit: Yomik Wei

Image credit: Yomika Wei

Image credit: Yomika Wei

Image credit: Yomika Wei

Image credit: Yomika Wei

Image credit: Yomika Wei

Image credit: Yomika Wei

We’re Jammin’

After a year of social distancing, what does the future hold for an art that relies on physical contact?

By Nuria Cremer-Vazquez

Contact improvisation (C.I.), a movement practice built on the fundamentals of touch, sharing body weight and spontaneous physical exploration, is a prolific string in the contemporary dance bow, with contact ‘jams’ being its prime site for artists to train and be choreographically inspired. At these events (pre-pandemic, of course), a dancer might insert themselves into a duet being improvised by strangers and play with lifting, counterbalance or bodily connection to create something new. But the UK’s contact jams are all off, and have been for almost a year.

Lewis Wilkins and Laura Lorenzi are two C.I. practitioners who live together, making them part of a minority who have been able to continue dancing with partners during lockdown. However, they tell me that for most people, the C.I. experience has been restricted to solo practice via online classes. What lies ahead when close proximity, the key aspect of a jam, is permitted again?

Image credit: Fabrício Lira

Image credit: Fabrício Lira

Image credit: Chris Yang

Image credit: Chris Yang

Image credit: Johnny Edgardo Guzman

Image credit: Johnny Edgardo Guzman

Image credit: Javad Esmaeili

Image credit: Javad Esmaeili

Image credit: Lewis Wilkins

Image credit: Lewis Wilkins

Image credit: Kazuo Ota

Image credit: Kazuo Ota

Under normal circumstances, one of a contact jam’s most appealing features is the range of proficiencies amongst those partaking. First-timers attending alongside professionals is not a faux pas, rather a signature of the style. But since no jams for a year has meant no newcomers to the scene, Wilkins says that “the practice is now restricted to the people that knew it already”. Perhaps it is to be anticipated that post-Covid jams will struggle to attract fresh faces and that regaining this core characteristic will take time. “Getting new people into it is going to be hard”.

Even once the government restrictions relax and interest recovers, it is clear that jams will be much changed on their return. It is a very real possibility that, to put people at ease, some organisers will continue to opt for a more regimented approach, maybe taking a leaf out of Germany’s book by implementing rules such as dancing with only a set number of people over the space of a month. But because it is the spontaneity and unpredictability of what happens at these events that makes them so delicious, limiting forecasts such as this leave a bitter aftertaste. “Spontaneity… that’s the thing that people will really miss”, says Wilkins.

However, it’s by no means all doom and gloom. In the wake of the BLM protests and with so much time for wider reflection, conversations have been had within the C.I. community about the inclusivity of the style regarding people from diverse backgrounds and diverse abilities. Lorenzi says this hiatus has offered an opportunity to rethink and optimise. “It is an inclusive practice. But perhaps not enough”.

Coronavirus’ impact on contact improvisation has certainly been paradoxical. As a dance style which, on the surface, was so incompatible with social distancing, those who practice it are potentially the most prepared for a future of adaptation and change. It is difficult to predict how long the small recoveries will take, but the government’s recent exit plan signals when these can at least begin. As you write your to-do list for the return to ‘normality’… could a contact jam be on the agenda?

now showing: not another pandemic movie

After the ordeal of last year, is there still an appetite for gritty cinema?

By Henry Southan and Shivani Dubey

Drama, horror and thriller are just three genres that would accurately describe the recent events of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, is there an appetite for these grittier genres on-screen after we finally wake-up from this nightmare? Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker told Radio Times, “I don’t know what stomach there would be for stories about societies falling apart,” and suggested that the public mood doesn’t suit another series of his popular dystopian anthology.

You would think that given the horrors the world collectively endured during the past year, people would not want to see the world ending on their screens anytime soon. But then you have movies like Contagion, that once upon a time seemed far-fetched, but have now become our reality. The renewed interest in this film in 2020 can perhaps be attributed to the harrowing similarities between its story and real life.

So that begs the question: will there be a shift in the type of content movie-goers want? Are we really tired of seeing the world end on screen time and time again? Or do we watch more of those to feel better about our current predicament?

Film academic Ray Kilby predicts that it will likely be similar to the trend that occurred after the second world war. “I think people will gravitate towards the lighter stuff first, followed by darker later. The same pattern was observed after the second world war. It was during the 1950’s when we started to look at the war. But immediately after and during, it was light entertainment.”

Film writer Jacob Mosha agrees that there may initially be less demand for darker genres as “it's clear to see that people are tired of this pandemic and seeing the terrible effects of it and they would welcome light-hearted entertainment.”

While on the other hand, film student Dhwani Gadh argues that “audiences don't really know what they want until they’ve seen it, so the demand as such might not change.” For example, 2020 saw the release of films like ‘Greenland’ and ‘Songbird’, both of which explore post-apocalyptic themes, the latter hitting closer to home in terms of the pandemic, yet they ended up gaining the audience’s attention.

On the opposing side of the argument, darker genres may not see a change in demand at all. Film writer Amber Rawlings observed that “historically, it seems that the horror genre in particular acts as a vehicle to explore contemporary anxieties and fears.”

She says that “the lockdown has bred a lot of anxieties, pertaining to health and the UK government, and for writers and directors, the darker genres may offer a way to explore those feelings.”

For example, in the past, Jordan Peele explored racism within the horror genre with his critically acclaimed, Oscar nominated classic ‘Get Out’. Similarly, the injustices and anxieties that were brought to light in the pandemic could be used as inspiration for future films. Rawlings adds that, “While more light-hearted films are a form of escapism, I think the distrust that COVID has instilled in our government and media might make us more dubious of genres like romance or comedy where it’s often a very idealistic vision being sold to you.”

So how soon is too soon to dramatise a notable or traumatic event? Jacob Mosha thinks even ten years down the line is too soon and could be seen as cringeworthy, “There's got to be a rest period for these things especially because films take a while to make and are always a reaction to something. So by the time these things come out, it could all be dated references and we'd have probably moved on to another thing altogether.” Rawlings suggests that those who suffered with their mental health might not want to see that time represented in a medium that’s otherwise a form of escapism for them, but for others it might be an illuminating experience to see that others felt the same and the subject is being given a platform.

Having said that, one thing is for certain: people miss the experience of going to the cinema and watching a movie surrounded by a group of strangers. No matter what kind of movie is playing on screen, people will flock to the theatres anyway, simply to be able to escape into another world again. As for movies about the pandemic, maybe it's time to move on, don’t you think?

Image credit: Victor Freitas

Image credit: Victor Freitas

Image credit: Anthony Shkraba

Image credit: Anthony Shkraba

Image credit: cottonbro

Image credit: cottonbro

Image credit: Norexy Art

Image credit: Norexy Art

Free money, Freer Arts

Rebecca Sibley argues that in order to rejuvenate the creative industries after the pandemic we need to fund them differently.

By Rebecca Sibley

Eighty-four years ago, France piloted a scheme that remains unique today. The intermittence du spectacle is a government-subsidised benefit for temporary workers in the creative industries. It pays them for every day they are unemployed between contracts. Initially introduced to attract tech crews for the growing cinema industry, it now supports around 250,000 theatre, music, dance and cultural workers. One circus performer, Kim Montels, told France24, “Without it, you might be performing every day, when you do things like circus or dance, your body wears out after a while. But with this system, it helps you last longer in your career.”

The idea of government benefits for creative industry workers is nothing new but Covid-19 has made the question of arts funding more urgent than ever. In Ireland, an arts and culture recovery taskforce has recommended that the government give an unconditional €325 per week to workers in the arts, culture, audio-visual and live performance industries. Individuals would receive this for the next three years in addition to their normal income. So far, it’s just a proposal. The Guardian argued in a recent editorial that big, bold ideas like this are exactly what we need in the UK.

In comparison to our government’s more limited support for the arts, the suggestion of funding creative workers for the next three years makes Ireland look like a utopia. Here in the UK, arts funding has been dwindling for a decade. Covid-19 has exposed the vulnerability of the creative industries which were worth $115.9 billion gross value added to the economy before the pandemic – more than the aerospace, automotive, life sciences, and oil and gas industries combined.

The UK government promised £1.57 billion in emergency grants and loans for arts and heritage venues last July and the 2021 budget will allocate another £400 million, but because a third of creative industry workers are self-employed this doesn’t quite cut it. As opera singer Allan Clayton wrote in The Telegraph, “Hundreds of thousands of freelancers like me… won’t see any of that money.” The government has also offered some (taxable) grants for self-employed workers, but many people have fallen through the cracks. If an individual became self-employed recently or makes too little of their income through freelancing they don’t qualify for the support, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has reported.

Meanwhile in France, the benefits of the intermittence du spectacle aren’t limited to people like Kim whose bodies need breaks from physically taxing careers. Studies have demonstrated a link between financial insecurity and cognitive abilities. One found that just thinking about a hypothetical financial setback lowered participants’ IQs by an average of 13 points, equivalent to the effect of a sleepless night or chronic alcoholism.

Another study found that a group of Indian farmers performed better in cognitive tests after the harvest when they had collected 60% of their yearly income compared to other times in the year when money was tighter. Like the farmers, work for people in the creative industries can be periodical and money tight. A system like France’s would benefit the bodies and minds of UK creative industry workers long after the pandemic; in addition to being a financial safety net it would mean they could produce better work.

In the US, San Francisco is trialling giving $1,000 a month to 130 local artists and culture workers for at least six months. Admittedly, it’s too little too late – a 2015 survey of arts workers reported that over 70% of respondents had or were being pushed out of the city by rising rents. Like the French scheme which has suffered funding cuts and the proposed Irish scheme that hasn’t yet become policy, the San Francisco pilot’s impact is limited because their government hasn’t fully committed to it.

Still, the existence of these schemes is important. They offer a hopeful glimpse of a future where art is funded because art is essential, where creative workers are given direct support to survive rather than encouraged to reskill. The twin threats of the pandemic and Brexit to the creative industries mean that it’s crucial to empower workers with reliable funding. France, Ireland and San Francisco are exploring new ways of supporting the future of the arts. UK, take note.

Sweaty bodies and spilled drinks: do we want pre-pandemic concerts back?

Rowan and Shivani discuss what they hope from concerts in the future.

By Rowan Howard and Shivani Dubey

Ever since the world descended into post-apocalyptic chaos, life as we know it came to a standstill. The entire world went into lockdown, pubs and shops were shut, people were barred from socialising and all major events and gatherings were halted for the foreseeable future. That included concerts. Concerts were one of the few places where you could come together with thousands of people and lose yourself in the music and the atmosphere of being able to witness some of your favourite artists live. But a concert is a lot more than just getting to see a musician. It is about the ambience, the mosh pits, the energy, the people and the connections you make with random strangers simply because you like the same artist. A concert is about community.

But, at the same time, it can also be about drunken brawls, sexual harassment, unnecessary fights, drunk and sweaty bodies pressed up against you from all directions, stampedes and near-death situations. So post-pandemic, should we continue to have socially distanced concerts? Especially given the logistical concerns that have risen ever since the COVID pandemic gripped the world? Or should we go back to the ‘normal’, whatever that may be.

Image credit: Marco Bicca

Image credit: Marco Bicca

Image credit: Hanna Tche

Image credit: Hanna Tche

Image credit: Shivani Dubey

Image credit: Shivani Dubey

This, however, may diminish the communal experience that concert-goers crave. Standing with just your friends, although enjoyable, takes away from the socialising aspect of the event. Some people attend concerts alone and this might make them feel more isolated, instead of feeling like they’re a part of something. Because even if you’re alone at a concert, you can rely on the fact that you’ll blend into the crowd and make friends with people in a similar situation as you. Unfortunately, being alone in that crowd might make you an easy target for harassment.

However, we are still in the middle of a pandemic where infections spread rapidly through close contact. If we immediately go back to the way concerts used to be, it could increase the risk of us falling right back into this mess again. So maybe it would be beneficial to start with socially distanced concerts and slowly ease back into the way things used to be, especially because some people are reluctant to immediately jump back into crowded spaces again. Perhaps it would help to experiment with the socially distanced model for a little bit. And if, along the way, we find a new way to retain the magic of concerts, without the groping and fighting, then maybe, just maybe, that could become our new ‘normal’.

Image credit: Petar Avramoski

Image credit: Petar Avramoski

Image credit: Fabio Traina

Image credit: Fabio Traina

One of the most invigorating things about concerts is the feeling of togetherness, especially in a mosh-pit – jumping and chanting with strangers, feeling the energy pulsate through them, to you, to the next person. Even if you don’t want to interact with strangers, the mere acknowledgement of their proximity makes you feel part of this reverberating collective, throwing praise to the god(s) on stage. The standing section is always the one that sells out first and for a reason – you want to be standing, alive, awake and ready to receive the presence of the artist you’ve been yearning for, for probably months on end.

On the other hand, mosh-pits are a breeding ground for sexual offenders and people looking for an excuse to fight. You are standing in a cramped space filled with sweaty bodies way too close for comfort, and it is the prime place for creeps and perverts to grope you without consent. With alcohol clouding their brains, people want to argue for no reason. Drinks spill, fights ensue, and someone almost always ends up getting hurt. At socially distanced concerts where people are stood in groups with their friends but a few feet away from other strangers, the risk of violence and harassment goes down significantly.

Image credit: Raul Jimenez

Image credit: Raul Jimenez

Image credit: Aditya Chinchure

Image credit: Aditya Chinchure

Rediscovering joy in uk communities

Georgina Collins meets two groups striving to bring creativity and joy to marginalised people across the UK.

By Georgina Collins

For the last year, despite lockdown restrictions and the ensuing chaos in all areas of British society, one dedicated organization called ODD Arts has been overcoming logistical barriers in order to visit prisons across the UK. The reason? Interactive theatre workshops.

Over six weeks, the organisation worked one-to-one with prisoners due to social distancing restrictions. The prisoners did trust exercises, took part in creative storytelling through mime and played word and memory games. These prisoners were considered extremely vulnerable, generally due to mental ill health, and this time offered a brief reprieve from 23-hour lockup.

After living in this “version of hell”, seeing the prisoners in a room “where they could express and laugh and have fun and connect was just amazing”, says Rebecca Friel who runs the small Manchester-based community arts organisation and coordinated these visits.

Creative industries in the UK are often criticised for elitism and being out of touch; a 2020 survey by Arts Council England (Ace) found that many people are uncomfortable with the term “the arts”, which they associate with opera and ballet. Community arts organisations which break down the barriers between “high” and “low” art have long been working to overcome these perceptions and make creativity more accessible for all across the UK.

This is ODD Arts’ mission; working in the criminal justice, education and community sectors they deliver theatre and creative art projects to address and explore challenging issues, particularly surrounding inequality, with vulnerable and excluded groups. They address knife crime, sexual assault, radicalisation, mental health and exploitation, giving those with lived experience of these traumas an empowering platform to express themselves. “Arts, culture and creativity can enable people to feel that they belong, give people a sense of freedom and safety, an outlet to be heard and a way to process challenging things,” says Rebecca.

Rebecca founded the organisation with two friends 17 years ago after graduating from Manchester University. The inspiration came from a period working with Augusto Boal in Brazil. Boal was the pioneering founder of Theatre of the Oppressed in the 1950s, a radical approach to theatre as a means of promoting social and political change where the audience became active participants.

ODD Arts have worked with Black Lives Matter activists who are campaigning to put a statue of Len Johnson, a black boxer from the 1920s in Manchester City Centre, by organising a theatre tour to educate people about the boxer's life. Another project, “Through My Eyes”, supported refugees and those who had been through the criminal justice system to put a theatre performance together. These two groups, who perhaps previously identified themselves as very different to each other, found that they had a commonality around the things that made them feel that they couldn’t fit in.

Community arts groups in many places have sprung up to bridge the divide where gaps in funding exist. Research by the County Councils Network (CCN) recently found £400m has been removed from culture and arts budgets since 2010, with some councils at risk of becoming “little more than social care providers'', as they reduce non-care services to the bare legal minimum.

This is what inspired Deborah Egan’s work for an organisation called DINA, a Sheffield-based inclusive and innovative arts organisation. It aims to provide a safe and welcoming space for everyone to enjoy and participate in artistic social initiatives that engage the local community. ”We recognise that creative subjects have been stripped out of the curriculum, it's a huge fault to think that people only need food and a roof, they also need creative stimulation, confidence building, and alleviation of mental health issues,” Deborah explains.

Deborah sees arts and culture as a means of expression that shouldn’t only be available to certain groups in society: “It is essential that there is that kind of irrigation of culture and it's available to everybody, not just people who could afford violin lessons”. Interactive art exhibitions, gigs, book readings and talks, comedy and more are all hosted at DINA. It functions as a hub for the LGBTQ+ community and hosts weekly meet-ups, as well as poetry nights and drag shows.

Deborah's aim is to provide a creative outlet for the poorer North West area of the city (Sheffielders who are born in poorer parts of the city live on average 10 years less than those who come from better-off areas). “Creativity is the last thing that’s considered, but it's about communicating and externalising anxiety and giving them the freedom to think imaginatively rather than when the next trip to the foodbank is.”

Boris Johnson recently announced that theatres and other venues could reopen from May this year, but the future of these community organisations is uncertain. “When we finally emerge and stand up and take stock of what has happened in the last year we're going to find it is a very blighted terrain. A lot of organisations have been unable to survive or have been stripped right down just to be run by one person half-time,” says Deborah. DINA and ODD arts have enough reserves to survive financially for another year, but beyond that is uncertain. Rebecca is used to this situation: “there’s already been years of cuts… every year we’d be looking at how do we cut back, how do we cut back” she says.

Both leaders hope that there can be a renewed appreciation of the value of the arts as the UK moves forward, from central government as well as ordinary people. Deborah highlights the significant economic contributions the arts industries make to the UK but she and Rebecca also agree that arts and creative industries will be a key way in which we process the trauma of the last year. The need for longer term and consistent public arts funding that will allow them to thrive, not simply survive, is their greatest hope for the future landscape of the creative industries in the UK. In the meantime, both are determined to get back to bringing music, drama and creative reprieve to people's lives. “Joy is the watchword,” says Deborah.

Image credit: ODD Arts

Image credit: ODD Arts

Image credit: ODD Arts

Image credit: ODD Arts

Image credit: DINA Sheffield

Image credit: DINA Sheffield

Image credit: DINA Sheffield

Image credit: DINA Sheffield

The future of your art

By Henry Southan and Rowan Howard

The arts industry in the UK has seen some major setbacks in the last year and at the heart of all this are the people who work to keep it alive. But what will this inclusive workplace look like for the future generation of artists? We asked arts students across the country about the impact the pandemic has had on their work and their hopes and predictions for the future of the industry post-Covid-19.

This is the future of the arts, through the eyes of the next generation of creatives...

has the pandemic directly affected your art and productivity?

100% of the students we spoke to said YES.

"Lack of motivation, tiredness but also it’s allowed me to think more and expose myself to more creative media which helps me be more imaginative."

“The pandemic and lockdown has affected my mental health and motivation , also the reduced contact and teaching from tutors has really affected my productivity this past year.”

“It's made it better - I am more focused than I have ever been and feel a sense of urgency I never have before.”

“My work is now centered more in my domestic space, the setting has changed therefore the subject has too. When I used to look outwards at the world from the bus or a cafe, I now look inwards, into my organs, body, emotions”

how can the government support your art post-pandemic?

“Actually putting funding and opportunities into the arts”

“By considering that art students are a valued part of the system and that they shouldn’t be dismissed just because they can ‘work from home’.”

“Reduced loan fees/better grants for post graduates”

“Refund studying years. It’s not worth £9000 for an online course.”

“Free/reduced prices on cultural events”

“Reduced rent and securing all internships are PAID. UK artists-passport for collaborative work and exchange with the EU.”

"Fee refunds, arts initiatives and funding, affordable studio spaces in London."

HOw can individuals support your art post-pandemic?

“By attending shows, supporting artists’ online sharing posts etc”

“Buying from individual sellers on Etsy (or other shops), exposing themselves to more creative media and encouraging others to do so as well.”

“Consuming art, specially from independent and small artists as opposed to big corporations”

“Not buying from Amazon, going to exhibitions, not being afraid to go out”

“Have discussions about art. Art is one of those things where "the more, the merrier" absolutely holds true.”

Lorna Dinning, Comic and Concept Art Student, Leeds Arts University

Divyangi Hadkar, Animations Student, Whistling Woods International

Kiana Smithdale, MA Performance Practices Student, De Montfort University

Helen Wilson, MA Sculpture Student, Royal College of Art

Unmasking the Arts was created as a way to look forward to the opportunities and challenges that will face the UK arts sector as the country moves beyond a year of lockdown.

Whilst writing, it became clear that though the future is far from certain, the capacity for creativity, fun and exploring challenging issues through art has not waned throughout our months in isolation. In fact, our biggest hope that it has been strengthened; and that after being absent for a year, there is a renewed appreciation of the UK arts scene in the future. We don’t have the answers for what this will mean in the long term, but the announcement of unprecedented amounts of funding to support the industry is a step in the right direction after years of chronic under-funding.

It may be a few months yet until we are able to go to the cinema, wander around a gallery or dance at a gig but that won’t stop us from making plans for the future.

We’d like to thank all of the artists, students, creatives, organisers, academics and fans who took the time to speak to us. This project would not be possible without them.

If you’d like to contact us about any of the individuals or organisations featured, please contact at unmaskingthearts@gmail.com

MEET THE CONTRIBUTORS

And see what they are most excited to do once the arts reopen again...

Georgina Collins, Editor

Be in crowded public spaces – galleries, concerts, festivals and more – maskless and carefree! I never thought I could miss making friends with strangers so much. And also see the Artemisia exhibition at the National Gallery in-person.

Twitter: @georginaihc

Email: georginac.freelance@gmail.com

Shivani Dubey, Production Editor

Go to the movie theatre and watch any movie that's screening – no matter how good or bad it is. I really miss the cinema! Also, go out for a nice lunch date at a cafe with my friends and catch up over a cup of coffee.

Email: shivanidubey2208@gmail.com

Rebecca Sibley, Sub-Editor

Step into a sparkling Yayoi Kusama infinity room at the Tate Modern, then spill half my pint on my shoes at an overcrowded concert later that night.

Twitter: @sibbrs

Email: rebeccasibley@googlemail.com

Nuria Cremer-Vazquez, Sound Editor

Awkwardly sidle past the other theatregoers to my mid-row seat at a West End show and buy an offensively-priced intermission ice cream.

Twitter: @NuriaAmaya_

Email: nuria.cremer@gmail.com

Yomika Wei, Production Editor

See the exhibition ‘David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020’ at the Royal Academy of Arts. Marvellous sunset, quince tree in the field, endless meadows…It is the time to celebrate the natural world and ‘new beginning’.

Instagram: @yomikawei

Email: yomikaweiofficial@163.com

Gracie Dahl, Illustrator

Draw in galleries again, trying to hide my sketchbook from nosy passers by. Also, see work by other people, to visit their exhibitions and studios and minds and feel inspired to make new work. Roll on opening back up!

Instagram: @graciedahl

Henry Southan, Audience Editor

Get roasted by a drag queen, buy overpriced snacks at the cinema and glug down a bottle of wine in a Soho jazz bar. -------------------------------------------

Twitter: @iamhenrysouthan

Email: southanhenry@gmail.com

Rowan Howard, Audience Editor

To be in the standing area at Rock City, close enough to the stage but far enough from the mosh pit, holding a beer that I don’t like and not knowing what to do with my other hand - and then the lights go down and everybody screams.

Twitter: @rlhowa

Email: rowlouhow@gmail.com