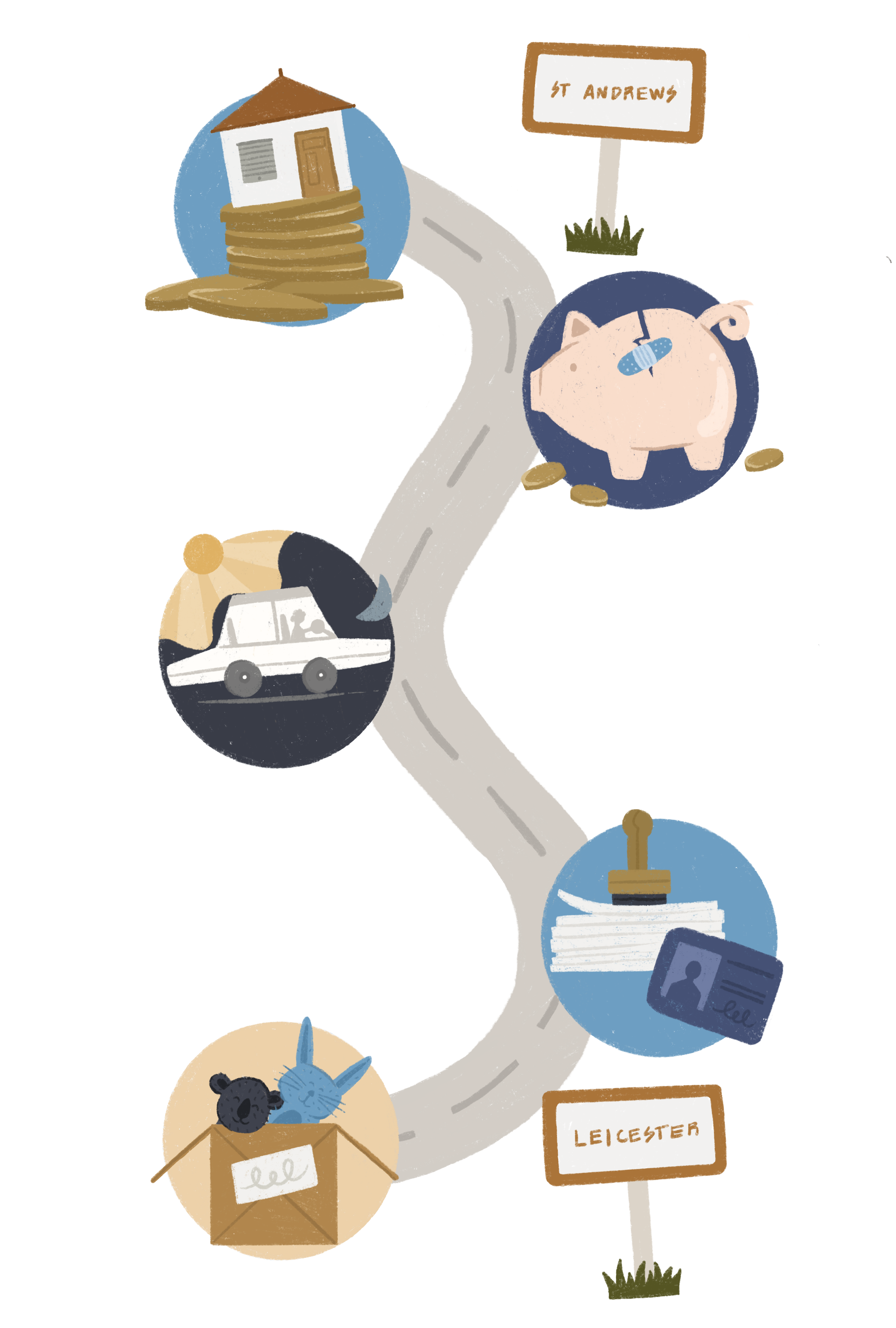

Five things I wish I’d known before moving house during a pandemic

Refugees face hidden barriers to making new lives in the UK – and for my family, these got much harder after the country locked down

By Ernest Zhanaev

Over the past year, a lot of media coverage has focused on the difficulties that lockdowns and social distancing measures pose for people moving home. While for most people it’s a task that requires careful financial and logistical planning, for refugees there are a host of extra difficulties.

When I moved house with my family, it meant leaving almost everything we had behind: a secure tenancy in council housing, not to mention all of the books, toys and furniture we had collected in the five years since arriving in the UK.

We moved from the East Midlands to Scotland so that I could improve my chances of employment, and to find a community tolerant of people of colour – especially one with a nursery where our child would not face abuse for being different.

So maybe it will have been worth it. I just wish I’d known the following things before we moved.

1. I wish I’d known how to deal with the benefits system better

The small one-bedroom council flat where we were living in Leicester was too crowded for a family of three. But we were faced with a difficult decision: try to find alternative accommodation in the city, or move elsewhere and lose our automatic entitlement to social housing.

The local council suggested we try house-swapping, but that didn’t work because we couldn’t find any tenants who would agree to swap with us. Moving away from Leicester would make it harder to get housing, but it was a way to improve my employment prospects.

My need was to improve my employability and cut a link to what some consider “being a second-class citizen” by relying on housing benefit. A secure tenancy, with part of our housing costs paid by the benefits system, was very comfortable but it didn’t give me the feeling of being properly settled in the UK.

When the pandemic started, social distancing only made us feel more isolated. But an offer to study at University of St Andrews in Scotland, with the support of a Sanctuary Scholarship, provided a new opportunity. Moving was a risk, but we had little other choice.

2. I wish I’d known to save money sooner

It’s good to avoid getting into debt, but it’s almost impossible for someone on benefits to save money. What’s more, moving to a different part of the country means temporarily losing housing benefit, and having to settle up with the council in the place you’re leaving.

Although we had some money for the 370-mile journey, we still needed to cover the removal of our remaining essential belongings, including our daughter’s toys and books. I receive a stipend for my university course, but there was a wait for the money to arrive in my bank account – and our low incomes meant we have no chance of getting a bank loan. Thankfully, my mother-in-law is a distinguished economist, and despite living very far from this country, she lent us the money, because she wanted to support our chances of social mobility.

3. I wish I’d known how difficult it would be to travel

In August 2020, when we chose to move, and when many lockdown restrictions had temporarily been lifted, we had two options for travelling to Scotland. We could go by air, which was surprisingly cheap, or by train, which was expensive as tickets were limited.

Unfortunately, we could only take the second option, because air travel requires photo ID and our refugee identity documents had expired. Because my course was due to start in the autumn, I couldn’t wait for them to be renewed.

Still, I think we were lucky to be able to travel and see new places, when others could not.

4. I wish I’d known how to get our documents sorted sooner

If you receive refugee status in the UK, your case is now usually reassessed after five years. Like many others, a decision on our application for further leave to remain was delayed by the pandemic. But I just couldn’t wait another year if I was to get on with studying and improve my economic prospects.

Since we’ve already experienced a range of temporary housing in various parts of England, the idea of trying to rent privately in Scotland seemed like a manageable risk.

While social housing has its own set of obstacles, private rented housing is tricky for refugees, as it is for other immigrants. A law that says landlords have to check the immigration status of prospective tenants has been accused of encouraging discrimination. Either way, many refugees get stuck: whether it’s living in council housing with limited leave to remain, moving from one place to another subject to the whims of legislators and landlords, or relying on friends for help.

5. I wish I’d known to do it while our daughter was still a baby

The Sanctuary Scholarship team helped us find temporary housing for mature students. That’s made it easier for my wife and I, but our daughter – Mia, who is five years old – really didn’t want to leave her old home behind. She didn’t even want to be parted from her possessions temporarily, while they were boxed up and sent to Scotland.

The first lockdown deprived Mia of nursery and friends, swimming, dance, and acrobatics classes, where she had excelled and was happy. It took Mia several months to regain her confidence and communication skills with her peers, thanks to the kindness and professionalism of nursery teachers who are used to dealing with children whose parents move house. We’re fortunate to have such support.

This pandemic will be over one day, and British citizens will be able to cross the country freely again. But for refugees, many barriers – some financial, some linked to their precarious immigration status, and some psychological – will remain.

Illustration by Daniela Di Martino and photographs provided by author

Ernest Zhanaev researches human rights issues in post-Soviet countries specialising in freedom of speech, social and political development. He was a human rights advocate in Kyrgyzstan.

Follow him on Twitter @ErnestZhanaev